Invasive plant species, sometimes called noxious weeds, are non-native plants that establish and spread readily and cause, or are likely to cause, environmental and/or economic damage. These plants are often introduced to new areas as ornamentals, crops, or as stowaways with human travel or trade. Peninsula Environmental Group works with private land owners and local municipalities to reduce and control invasive plants throughout Western Washington. We also see infestations of invasive plants during our environmental assessments and while exploring our beautiful outdoor areas.

Invasive plants come in a wide variety of species, sizes, and habitat types, but tend to share several characteristics. They, in some way or another, are highly adapted to establishing and spreading quickly. Some produce incredible amounts of seeds, others spread through rhizomes or small fragments, and some have seeds that persist for decades in the soil. They also tend to lack the same biocontrols (pests, pathogens, etc.) that kept them controlled in their home ranges, allowing them to grow uncontested while native species are naturally suppressed. Some simply grow faster or more vigorously than native plants and out compete them for limited space and resources.

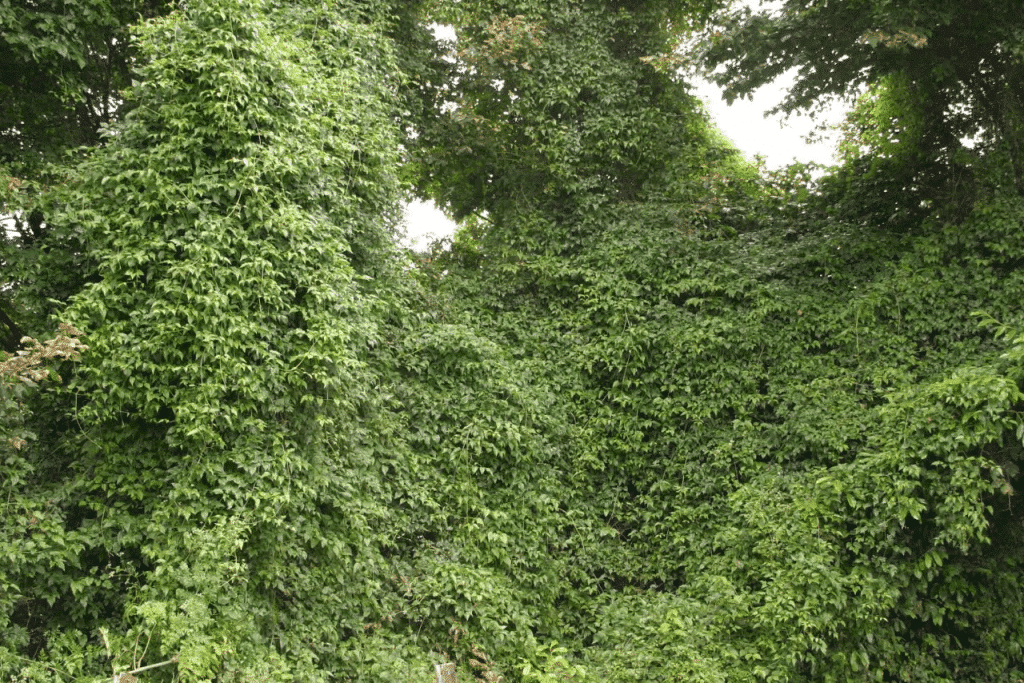

While our native ecosystems are

varied and diverse, there are still communities of plants that we regularly see

together. A dense coniferous forest with a primarily salal and sword fern

understory. A wetland fringed by willows and douglas spirea. A meadow with Garry

oaks and wildflowers. A seasonal stream with overhanging salmonberry and cedar.

The list goes on, and each community can have site specific variations. These

communities provide a plethora of services that the local fish, wildlife, and

insects come to rely on. These systems can, and often do, have non-native

plants that exist within them. The issue begins when these non-native plants do

not exist in balance with the native system. These disturbed systems are the

types of plant communities we are seeing all too frequently now. Complete

monoculture of Himalayan blackberry in a field that was cleared and left alone.

Heavily disturbed right-of-ways with nothing but scotch broom. Mixed coniferous

forest with an understory consisting of a blanket of English ivy that has

already engulfed several trees.

Four of the most prolific invasive plant species in our region are English ivy (Hedera helix), English laurel (Prunus laurocerasus), Himalayan blackberry (Rubus armeniacus), Scotch broom (Cytisus scoparius). No doubt you have seen these species in your travels, both in disturbed areas where they can easily establish, as well as more natural areas where they have invaded. These species are known noxious weeds, but are not mandated for removal by Washington State because the state itself cannot control the spread on their own lands, and so cannot force private citizens to do so. They, as well as many County Noxious Weed Boards, do strongly advocate for their removal and provide information on how to identify them and remove them on your own property. However, without a concentrated effort across the entire region it is unlikely that these species will slow their spread, and we will continue to see them displacing native plant species in nature.

Why does this matter? A plant is a plant is a plant, right? Not so much. While having any vegetation is often better than bare ground or impervious surfaces, a disturbed ecosystem dominated by invasive species is not the same as a naturally occurring native plant community. There are valuable functions that are lost when the plant communities that have been stable for generations are traded for the invasive species humans have introduced. This is not a natural migration of species. Fish, wildlife, insects, and other plants have evolved around each other in our native ecosystems.

There are specific phenological timings, habitat requirements, and community structures that are thrown out of whack when a large infestation of invasive plants take over. Where an early successional forest of alder would normally give way to a mixed coniferous forest, a heavy blanket of English ivy or Himalayan blackberry stifles the juvenile conifer growth. With the loss of those native plant communities comes a loss in ecosystem functions like habitat (food, shelter, nests, etc

What can you do? Despair not! You have the power to help combat the spread of noxious weeds. As we’ve discussed in several other blogs these macro-invasives and the practice of integrated pest management (IPM) focuses on reducing noxious weed presence through a number of means. It is then critical to follow up the removal of an invasive species with the establishment of a native plant community. This provides the dual purpose of returning lost ecosystem functions as well as hindering the ability of noxious weeds to become reestablished. Check out your local Counties Noxious Weed Boards for information invasive plant species in your area, and what to do to combat them. Check out some of the resources below for information on the four invasive mentioned in this blog. As always, feel free to reach out to Peninsula Environmental Group with any questions regarding noxious weed control, restoration, or our native plant communities.

Invasive Plant Learning Resources: